Singapore business cyber confidence is probably cyber delusion

"Singapore companies are confident of their ability to detect a sophisticated cyber attack," read an enthusiastic press release earlier this month. "80 percent of the Singapore respondents share that sentiment, surpassing the global average of 50 percent."

On face value, that sounds like a big thumbs-up for doing business in Singapore. But let's dig down into this.

First, though, some background.

The press release was from the Singapore office of EY -- that's the global brand of the various companies in the Ernst & Young group -- and the figures are from their report Path to cyber resilience: Sense, resist, react: EY's 19th Global Information Security Survey 2016-17 (GISS).

The report is classic of the corporate cybersecurity genre. Download the PDF and you'll get 38 richly-designed pages. These reports always have a visual theme, and for this one it's lush full-page photos of sea critters. Pretty.

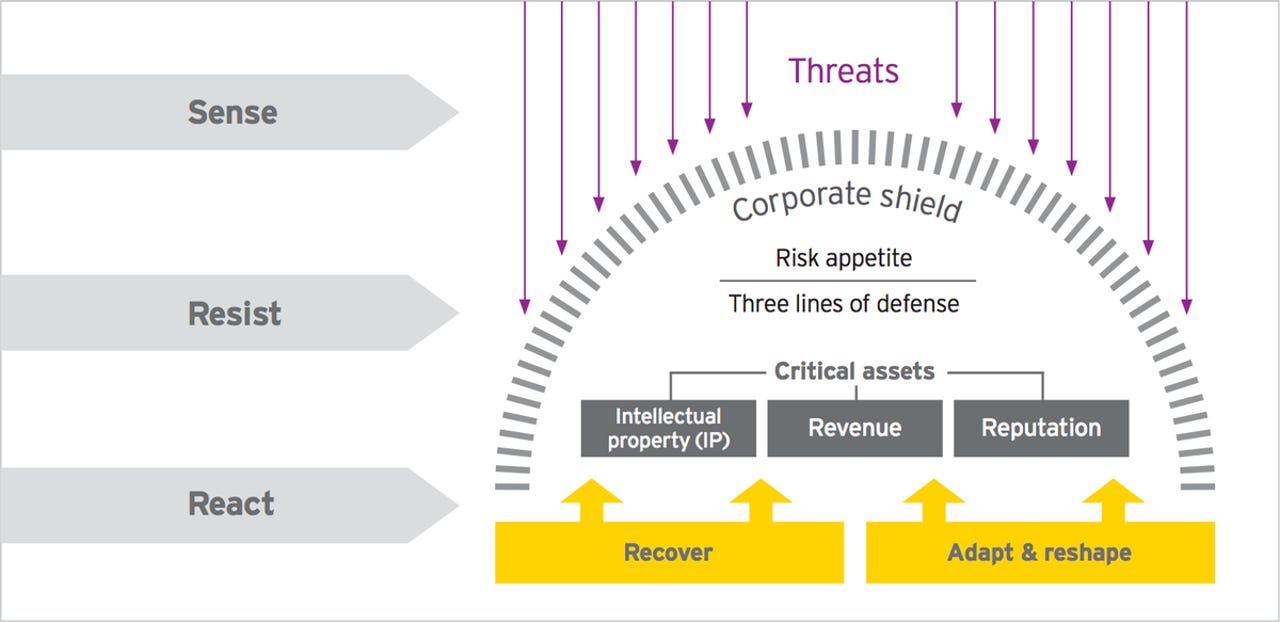

These reports always include a diagram that explains the concepts the company is trying to sell you. In EY's case, it's their three high-level components, matched with three lines of defence.

"Sense is the ability of organisations to predict and detect cyber threats. Organisations need to use cyber threat intelligence and active defence to predict what threats or attacks are heading in their direction and detect them when they do, before the attack is successful," EY wrote.

EY's view of the three high-level components of cyber resilience.

"Resist mechanisms are basically the corporate shield. It starts with how much risk an organisation is prepared to take across its ecosystem, followed by establishing the three lines of defence."

The three lines of defence are: Control measures in the day-to-day operations; monitoring functions such as internal controls, the legal department, risk management and cybersecurity; and a strong internal audit department.

Latest news on Asia

They're similar to the three lines of defence cited by Victoria's Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) in its investigation of the failed Ultranet project.

"If Sense fails (the organisation did not see the threat coming) and there is a breakdown in Resist (control measures were not strong enough), organisations need to be ready to deal with the disruption, ready with incident response capabilities, and ready to manage the crisis," EY writes.

Older information security practitioners will recognise this as a reordering of the classic protect, detect, and react paradigm for infosec. That's been around for 20 years or so, and more recently a fourth step has been added: Recover. EY has rolled that back into React.

There's nothing new here, apart from the names of each step.

Finally, EY asks the question: "Cyber resilience or cyber agility?" Their answer is that you need both, which cleverly means that no buzzword is left behind.

With that background in mind, let's look at the numbers. I'll use the Singapore figures, since they triggered this little investigation, but EY's full report lists the global averages.

That 80 percent of Singapore respondents I started with agreed with the proposition that they were "likely" to predict and detect a sophisticated cyber attack.

That's better than the global average of 50 percent, sure. But "likely" is not "definitely". It still means 20 percent of Singapore's businesses think detecting an attack is unlikely. And detecting is not the same as preventing.

More importantly, this survey measures what the respondents think about their organisation's abilities. It's not a measure of reality, it's a measure of feels.

Taking that on board, though, the rest of their feelings are revealing.

Some 85 percent of Singapore respondents say their cybersecurity function doesn't fully meet their needs; 80 percent say they lack skilled resources; and 60 percent are hampered by budget constraints.

Poor user awareness and behaviour around mobile devices concerns 80 percent of Singapore respondents, with 60 percent of the respondents citing the loss of a smart device as a top risk.

This doesn't add up. It means there's a big chunk of Singapore businesses with real concerns -- like the 85 percent that say they don't have what they need -- but at the same time have confidence in their defences.

You can't have it both ways.

"This is fine, but yeah nah it's not. We need more money."

Guys, you're deluding yourselves.

EY is also deluding itself. It confidently compares the Singapore figures with the global averages. But with all such reports, the very first thing you should do is look up the value of N.

"The survey of 1,735 organisations globally (including 20 from Singapore)..."

Right.

For the global figures, a sample size of 1,735 gives you a standard margin of error of around plus or minus two percentage points. That's useful in many, if not most, circumstances.

But when you split out a mere 20 respondents from Singapore, the margin of error rockets to plus or minus 22 percentage points.

You say 80 percent of Singapore businesses are confident, EY? Really? The best you can say is that it's somewhere between 58 and nearly all of them.

The report doesn't say, and I'm not really a betting man, but I'm willing to put money on this being a self-selected sample -- that is, the respondents are whoever had the time and enthusiasm to bother. From a statistical point of view, that makes the whole thing meaningless.

This isn't research into a global reality. It's a hand-wave of a guesstimate of random people's feels. Just like nearly all such reports.

That sounds pretty negative, and it is, but the report does have some value.

There's nothing really wrong with EY's framework, and it's useful to freshen up the language from time to time so executives pay attention. And the section, "Key characteristics of a cyber resilient enterprise" is a useful checklist for strategic planning.

Of course, the real purpose of such reports is to sell services.

"Organisations need to use cyber threat intelligence and active defence to predict what threats or attacks are heading in their direction and detect them when they do, before the attack is successful. They need to know what will happen, and they need sophisticated analytics to gain early warning of a risk of disruption," EY wrote.

Why? Who says so? What evidence do you have that says organisations that do this have demonstrably fewer or less serious data breaches or disruptions to service? All you've got is that some uncertain number of organisations feel safer if they spend the money.

Now there's nothing wrong with marketing your services, and I'm sure this report will help EY in that endeavour.

Still, you'd think a Big Four accounting firm with revenues of $29.6 billion would know how numbers work.